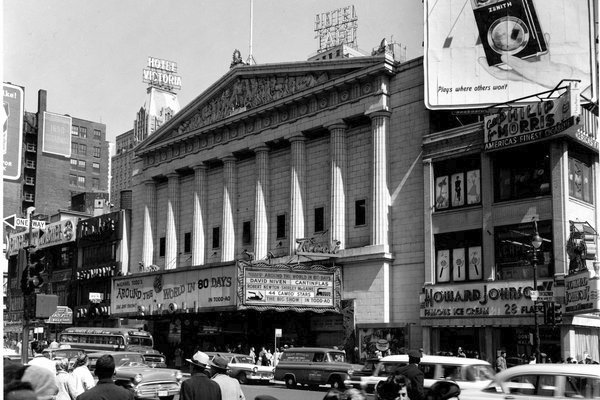

The 1917 Rivoli Theater at Broadway and 49th Street in 1958. In 1986 the Doric facade was deGreeked; demolition occurred the next year.

Published: July 18, 2013

It’s an ugly job, but somebody’s got to do it: stripping buildings of decoration to avoid any last-minute obstacles to demolition. The most recent instance is an unusual three-story limestone mansion at 60 East 86th Street, built in the Eisenhower era by a chiropractor/art collector but now on a site being readied for new construction. The limestone molding, trim and cornice have been hammered off.

The history of stripping buildings in New York is a long and ignoble one and, in the case of buildings that weren’t landmarks but maybe should have been, poses the question: who is the guilty party, the owner who calls in the jackhammers, or the preservationists who are caught napping?

And in these situations, yet another question often arises: not whether opposition to the demolition might have cropped up, but why the developer was ever worried about opposition in the first place.

In 1976 I boiled with righteous, 20-something indignation over the desecration of the innocent little Cherokee Club, at 334 East 79th Street, a Tammany Hall outpost built in 1890.

It was a chunky Romanesque assemblage of round arches, rock-faced brownstone and stubby columns. When a developer, Louis Evangelista, moved to redevelop the site, some residents tried to get the Landmarks Preservation Commission involved. While a meeting with Representative Ed Koch was pending, Mr. Evangelista hired a demolition crew, and the facade emerged with the mug of a prizefighter who always went 10 rounds, but lost.

The developer said that the Department of Buildings had ordered the removal of “all hazardous ornamentation and decoration,” which it had not. Representative Koch fumed that “it was perfectly legal, but reprehensible.” The new building went ahead.

No matter, really, because although the Cherokee Club was a pleasant, provincial work, it was miles away from what the Landmarks Preservation Commission was designating at the time, and the developer had no reason to be concerned.

A particularly gruesome mutilation was the one visited on Thomas Lamb’s 1917 Rivoli Theater, once at 49th and Broadway. Lamb did not literally reproduce the Doric facade of the Parthenon, but on busy Broadway it was certainly close enough.

The white glazed terra-cotta facade lasted until 1986, when the owners destroyed a column and beheaded the top — gods, classical drapery, chariots and all. At the time, preservation groups were focused on the stage theaters; the Rivoli was built for film, and it was not on anyone’s radar until the bucrania were out of the barn.

For me, it got personal two years later when Sherwood Equities ripped off the sumptuous copper cornice of the 1902 Studebaker Building, at Broadway and 48th. That’s because I am a descendant of Peter Studebaker, a member of the wagon-building family that switched to electric vehicles in 1902. (Smug disclosure: I now drive a Studebaker, a 1950 Starlight Coupe.)

The remarkable high-rise combination-automobile-factory-and-showroom was designed by James Brown Lord, prominent in his time, and it was the largest vehicle-related structure to go up in what had been originally known as Longacre Square, after the London carriage district.

In December 1988 Sherwood Equities filed plans to “repair ornamental cornice,” and then repaired it beyond repair.

But Sherwood could have proceeded without benefit of brutality to the realization of what is now the tower at 1600 Broadway, because in its survey of the area, the Landmarks Commission misdated the building, missed the Studebaker name, failed to identify the automobile connection and misidentified the architect, and so considered it just another loft building.

At hand now is the limestone town house at 60 East 86th. Anton Meister, a chiropractor and art collector whose resources, according to a 1966 New York Times account, were “seemingly unlimited,” built it in 1956, with the architect James Casale, otherwise known for modest alteration work. The construction of large private houses is rare enough in the 1920s; it’s icicles in the desert in the 1950s.

Last year, advertisements for the sale of the 86th Street site stressed its freedom from landmark controls. The new owner, Glenwood, took no chances: after submitting plans last month for “remedial repairs,” it proceeded to remove any conceivable decorative embellishment.

Glenwood officials declined to comment on the matter, as did Stephen B. Jacobs Architects, which is designing the 19-story building to go up on the site.

But the remedy was not necessary; the Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts, the Historic Districts Council, Carnegie Hill Neighbors and even the Landmarks Preservation Commission say they know of no potential landmarks on the block.

Glenwood has a demolition permit. And the house has been sitting there in the wide open for decades, so no one can say it didn’t have a chance.